- Scaling can be measured at different levels: Scaling the Dev team, scaling-out (more hardware), and scaling up (making each server count).

- Scaling-out was achieved by expanding to multiple data centres. Disaster recovery is taken seriously at Facebook: Drills (data centre outages) were performed regularly.

- Two criteria for scaling-out: Storage and computing.

- Storage needs to be consistent across data centres. Computing grows based on user traffic.

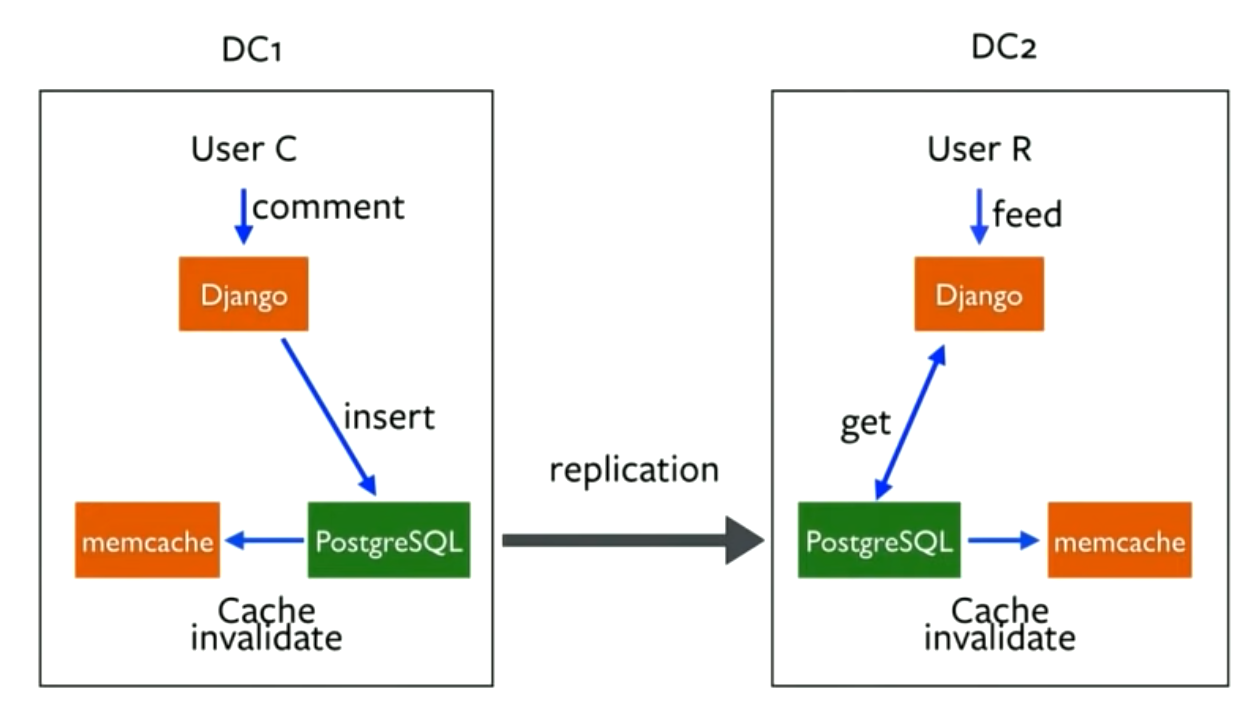

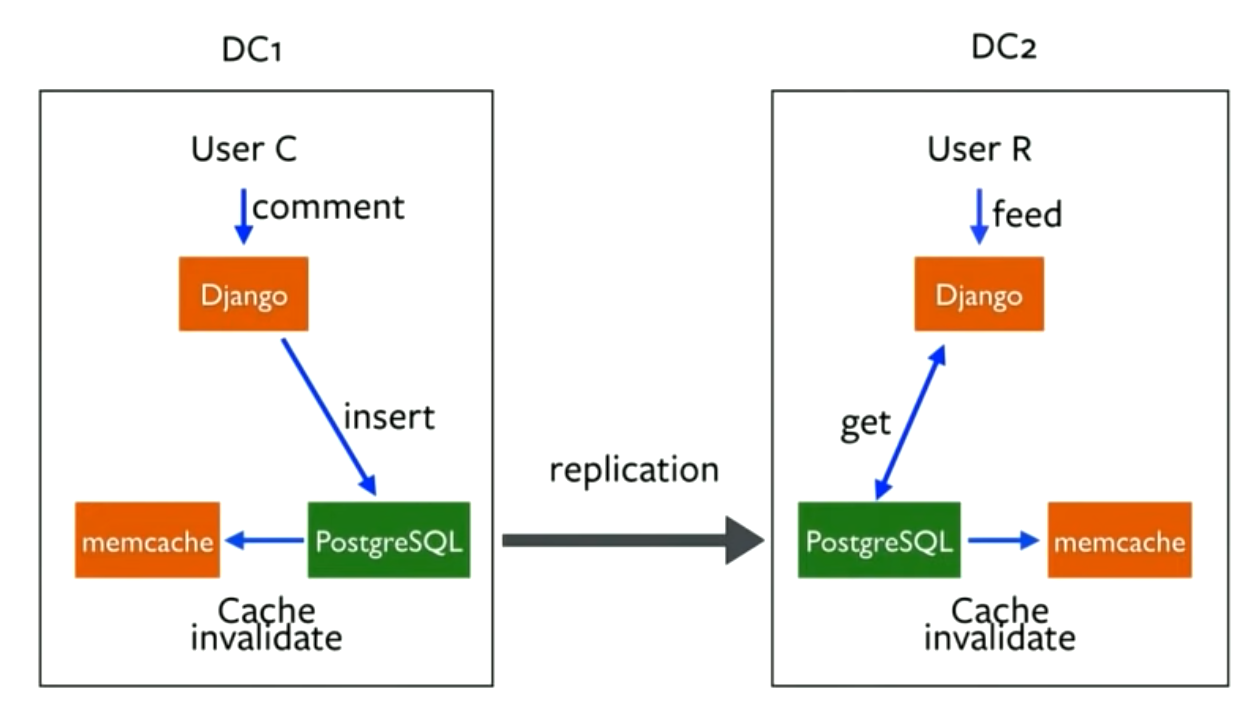

- Django reads from the local Postgres DC replica and writes to the master instance (often in another DC). User feeds and activities are stored in Cassandra, which has no Master instances.

- No global consistency for Memcache as it is very sensitive to network conditions, and thus cross-region operations are prohibitive.

- Requests are hashed based on UserID. Two users sitting next to each other may end up in different regions, and thus the second one may get stale values from the other Memcached. This is solved by invalidating the local Memcached when Postgres is updated.

- The invalidation is not done for some cached information (eg. number of likes), as the load on the DB was too high otherwise (invalidating the cache on each like).

- To solve the issue of the thundering herd after a cache invalidation, Memcache Lease is used: Successive reads would get a “wait or stale value” response, while the first reader fills the cache from the DB. This would reduce the load on the DB.

- Scaling up: Don’t count the servers, make the servers count.

- Perf events are used to collect data on CPU usage. It’s aggregated based on which features are enabled for a request. Python Cprofile is used to analyse the data, and visualize which functions use the most amount of resources. Certain functions were rewritten in C based on the analysis.

- In order to run as many processes as possible on each server, the memory footprint has to be reduced. Part of that is reducing the code size (running with -O optimization, eliminating dead code…). Also, more data such as configuration is moved into shared memory processes while measuring the tradeoffs (as it would be slower than using private memory).

- Network latency: Synchronous processing in Django (each process can handle one request at a time). To reduce the latency, async IO for multiple endpoints at a time was explored to reduce the wait time.

- To scale up the team: Building an architecture that handles caching automatically, where developers define relations not implementations, and that is self-served by product engineers, to let the infrastructure engineers focus on scaling.

- A single-branch model is used for source control, to provide continuous integration and easier collaboration. As all changes are merged to Master, features gating is used to roll out changes and load-test them. This still leads to 40-60 rollouts per day, which happen over multiple steps (unit tests and checks, canary…) to ~20k servers in ~10 minutes.

- Slack had issues scaling its infrastructure in the early days (2016) due to most engineering being product-focused.

- As the usage grew, new challenges had to be tackled. User presence was around ~80% web traffic, as it was implemented in a broadcast way (to all users in the workspace) which was O(N**2). Switching to a pub/sub model reduced this significantly.

- There were organizational growth challenges as well, such as getting enough resources and headcount. Evangelism for building the infrastructure-engineering organization was necessary while following the company’s processes (planning, reporting…) and finding an executive sponsor.

- Phase 2 (2017) was about moving from the Hack/PHP monolith and experimenting with building services in Go. The monolith caused ownership and communication issues (who owns which parts of the API/SLA, how to communicate underlying changes that affect the services using it…)

- MySQL DB sharding was done per workspace/team, which hit the scaling limits (very hot shards), and had to be transitioned to YouTube’s Vitess, sharding by various keys.

- Phase 3 (2018) was about scaling from a few teams to a larger org in multiple offices, hiring more specialists, and explicitly defining SLAs for services.

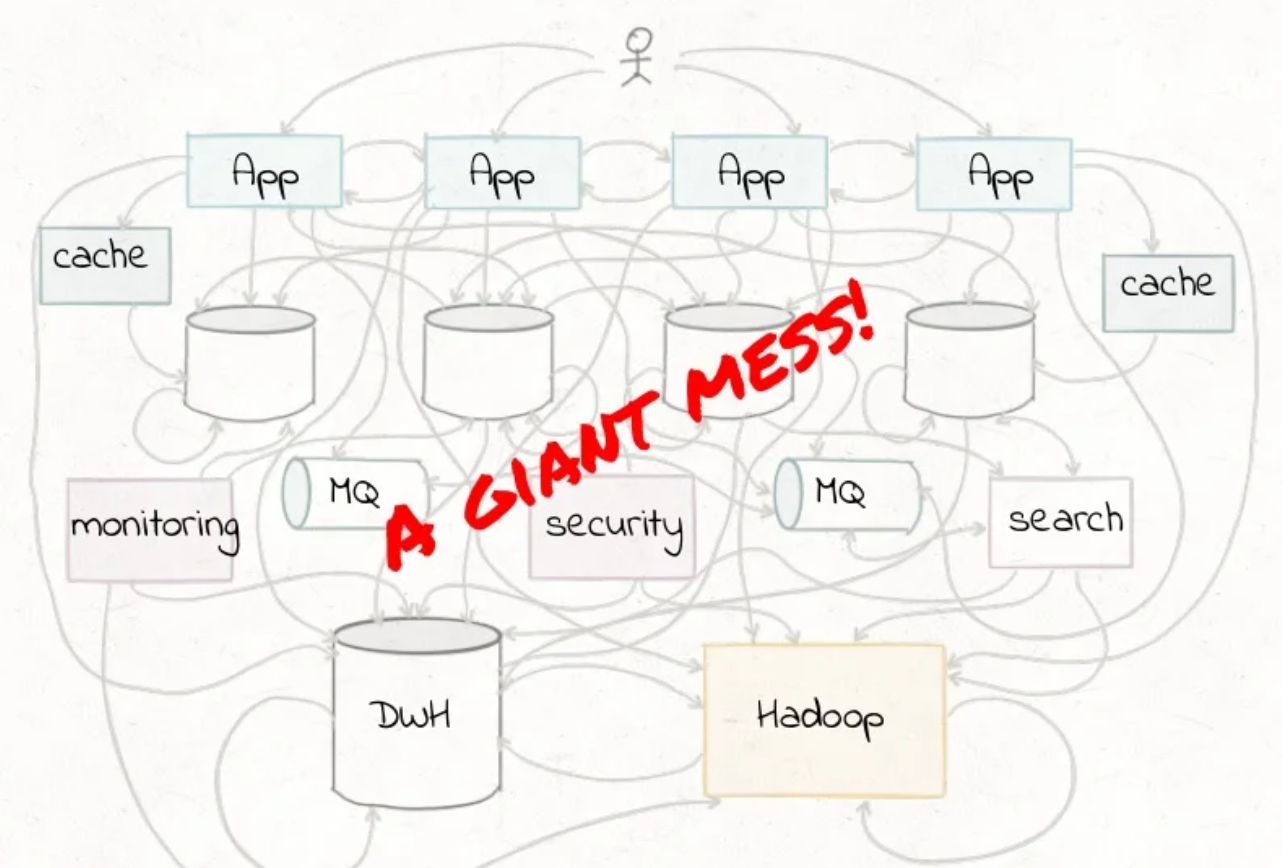

- Old world: Data was either in DBs (operational) or in the warehouse (histortical / analytics). Data didn’t move between them more than a few times a day.

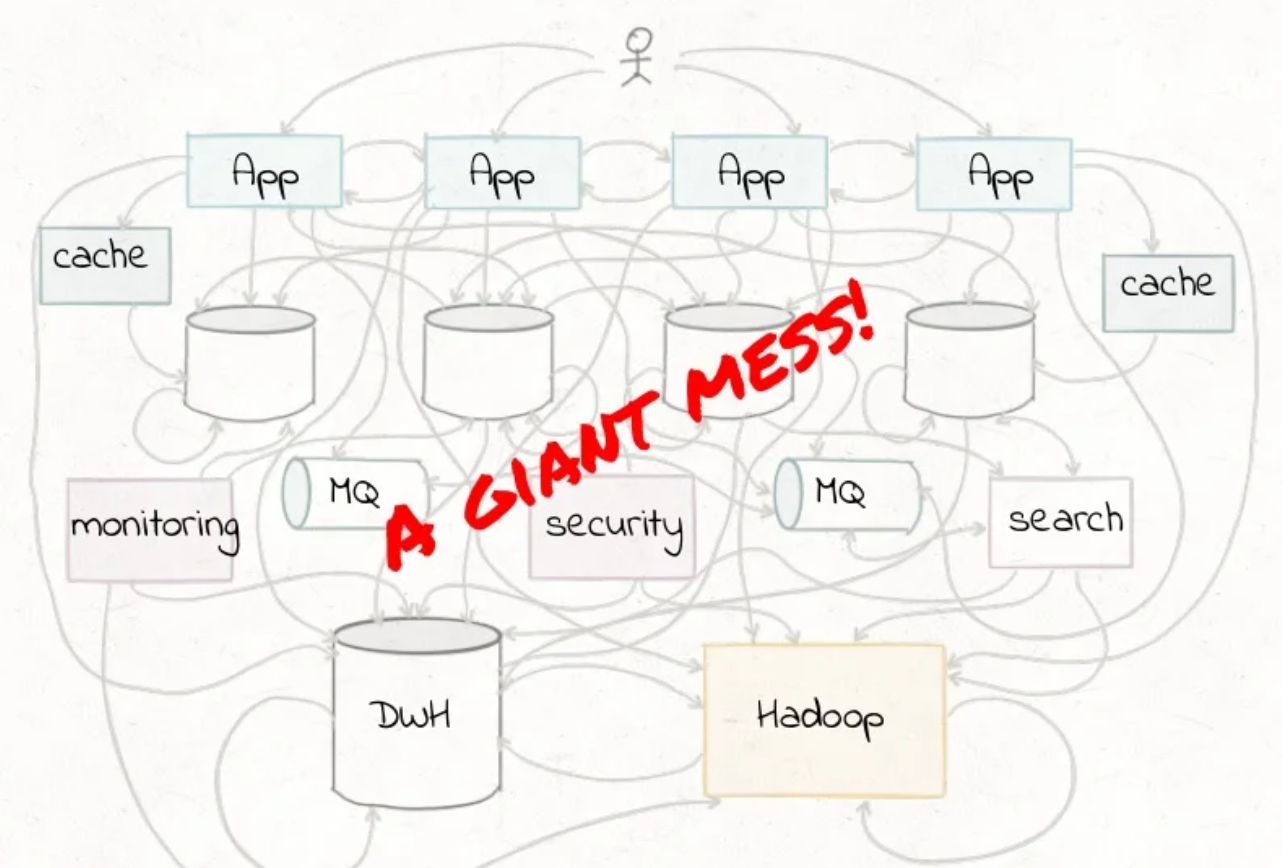

- This is challenged by new trends: Distributed data platforms at a company-wide scale, different data types beyond transactional (logs, metrics…), and stream data being more common and needing faster processing.

- ETL: Extract from databases. Transform into destination warehouse schema. Load into central data warehouse.

- ETL is scalable but has many drawbacks: Requiring a global schema for the data warehouse, manual and error-prone data curation and a high operational cost (time and resource).

- EAI (Enterprise Application Integration) is real-time (using Message Queues) but not scalable.

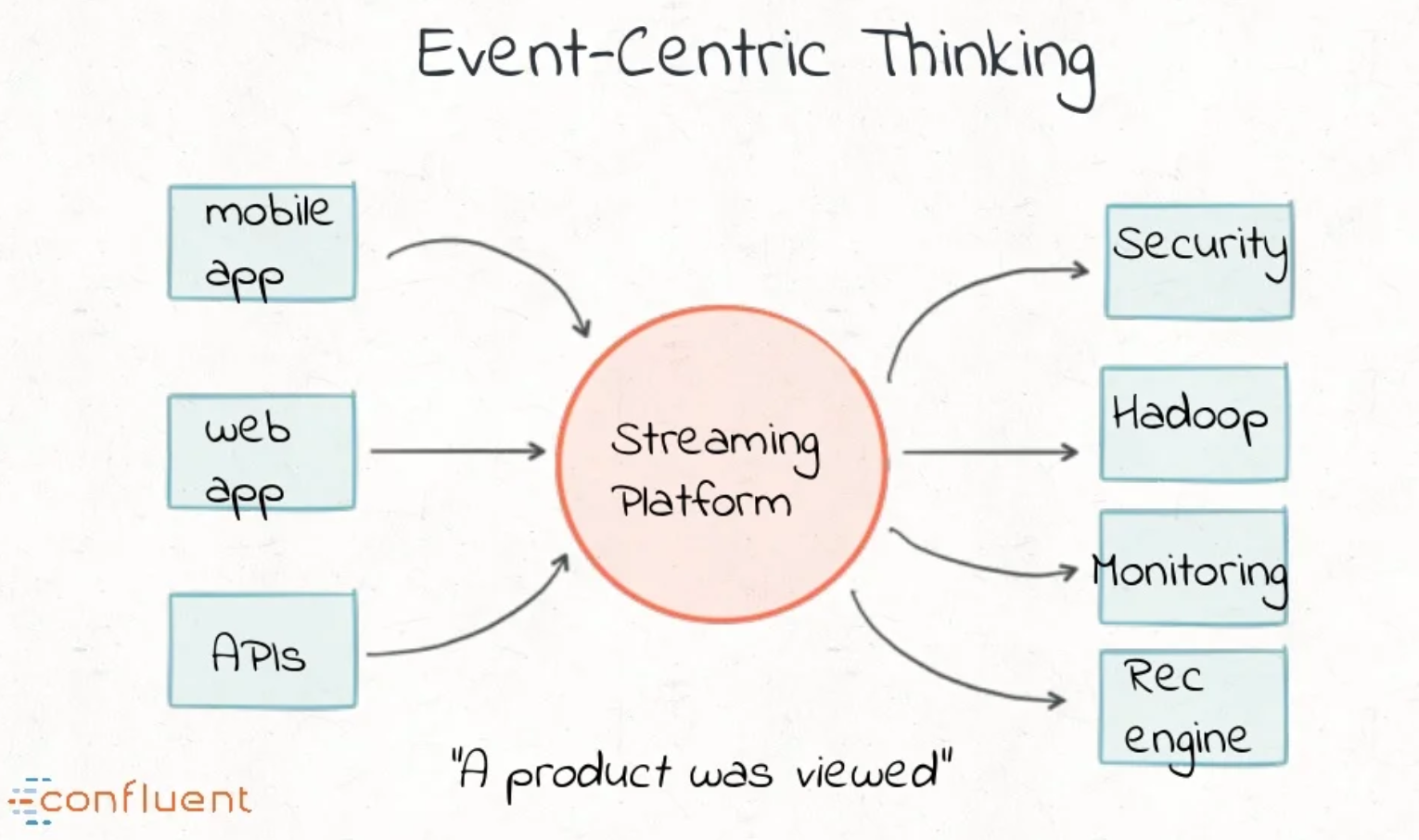

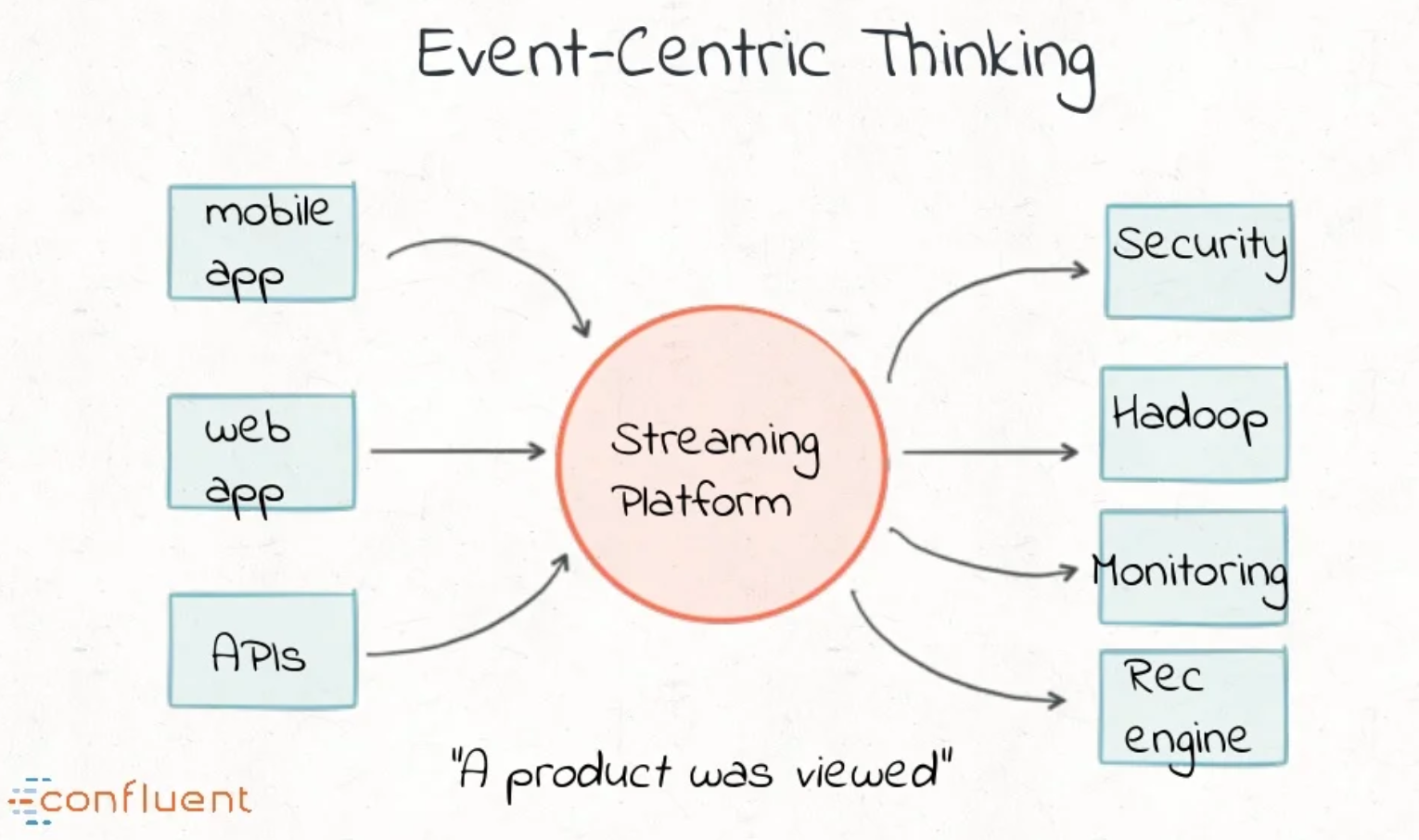

- Modern streaming requires real-time support with an event-centric thinking.

- To make data forward-compatible, the T in ETL should transform data only, and not cleanse it.

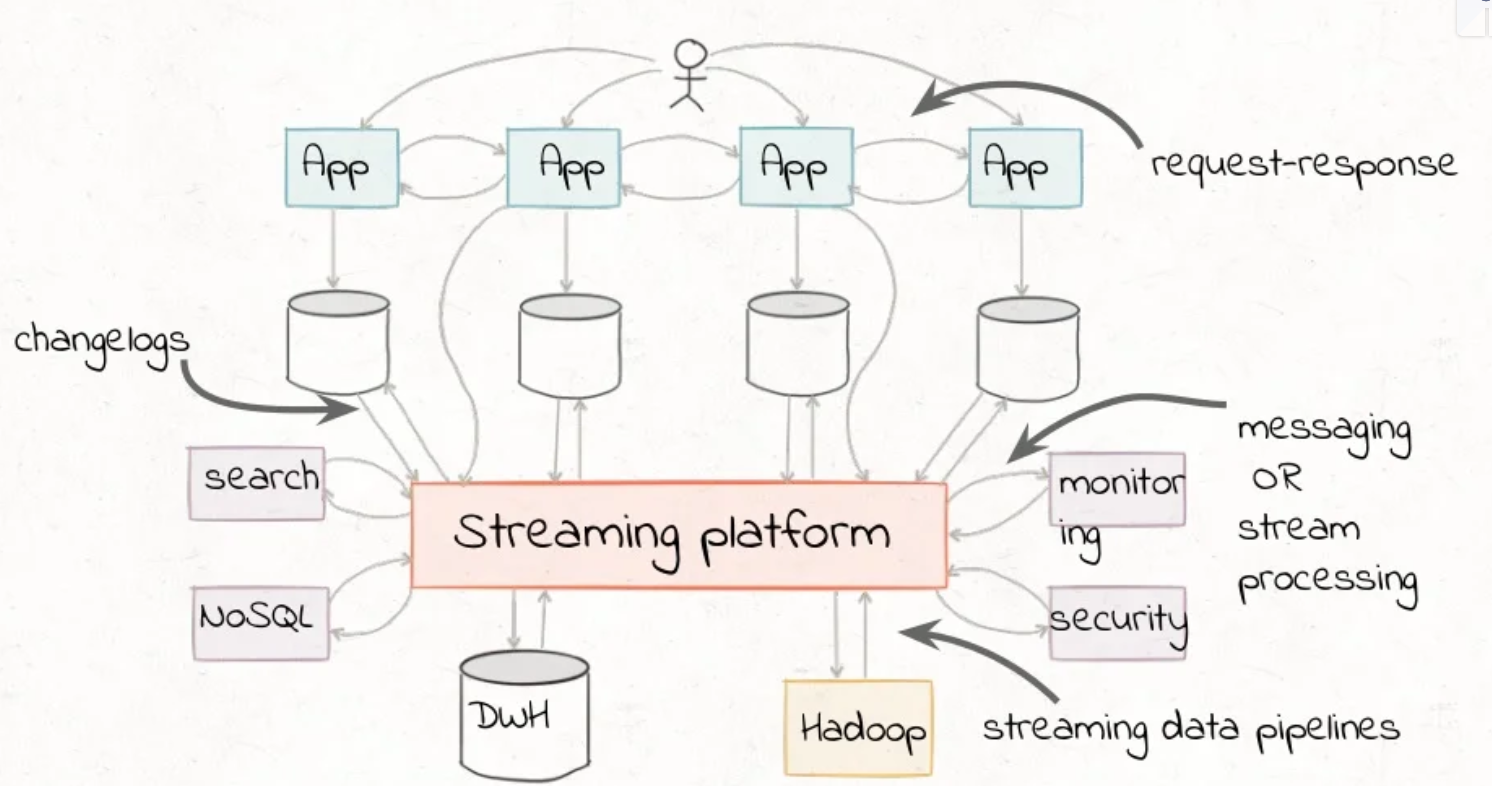

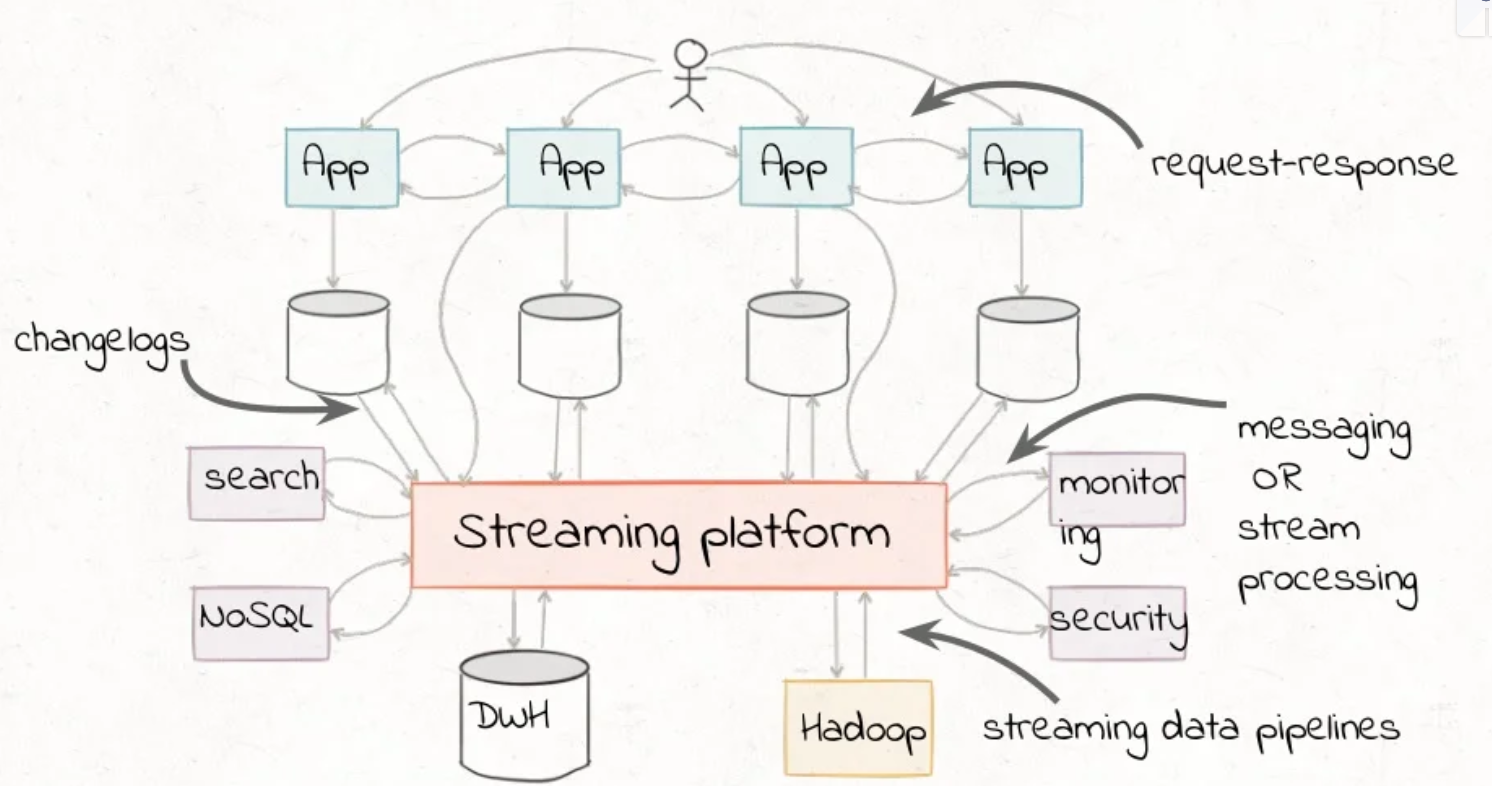

- The streaming platform will serve as the real-time messaging bus, the source-of-truth data pipeline and a building block for stateful processing services.

- Apache Kafka is the de-facto choice for stream data storage. The Log abstraction, allows persistent, append-only, replicated and write-ahead log. It’s a great for building scalable PubSub messaging. Publishers append the data, and subscribers read and maintain their own offsets.

- Kafka’s Connect API allows building the Extract and Load abstractions. The Streams API allows transforming the data.

- Logs unify batch and stream processing on the same re-usable abstraction.