Depth of Code

Hani’s blog

Hani's Weekly 3: #2

How does SQLite work?

- SQLite databases are organized in fixed-size pages. Historically, this page size was 1KB but was changed in 2016 to 4KB in order to accommodate better with modern hardware.

- These pages are stored as BTrees: Data is stored in leaf pages, but not interior pages.

- As disk I/O is expensive, it makes sense to read as few pages as possible. Thus, a BTree with more children nodes will lead to fewer node reads.

- Each table in the database has a BTree. But an additional BTree is maintained for each index on the table. This is why maintaining multiple indices is slow: On row insertions, multiple BTrees are updated.

Patterns of Distributed Systems

-

One of the challenges of teaching distributed systems is how to bridge between theoretical concepts and practical open source solutions such as Kafka. Using pattern structures makes those practical solutions easy to understand.

-

Distributed systems are inherently stateful systems because they manage data. They vary in size from a few nodes to a cluster of hundreds of servers.

-

Process crashes: These can happen at any time due to software or hardware faults, maintenance, unrelated events bringing the server down, etc,.

- The process should provide durability for the data it notified the user that it has been stored successfully. Because flushing every data update to disk is time-consuming, most databases include in-memory storage structures that are routinely flushed to disk.

- Write-ahead log is a technique used to ensure durability by storing data updates as commands in a write-only log file. This operation is fast enough to not impact performance. When the service is restarted, the log is replayed to rebuild the memory state. This provides durability guarantees but still lacks service availability when the server is down.

-

Network delays: There are two main problems at hand here:

- A server can’t wait indefinitely for another server to respond. This is tackled by sending heartbeats at regular intervals and continuing service without the server that is missing heartbeats.

- A quorum helps to survive some failures but doesn’t provide strong consistency guarantees. It would be possible to update values on the quorum and still read old values from the minority servers. Thus, propagating values via the leader/follower model is needed. A high-water mark in the log file is used to mark which values were propagated successfully, which means that there are no inconsistencies later if a follower is elected as leader.

-

Process pauses: If a leader is temporarily unavailable (eg. garbage collection pause), followers may elect a new leader. Generation clocks, a monotonically increasing number that keeps track of leader elections, can be used so that the old leader detects that they have to step down from leadership. The follower can detect that the old leader’s generation is too old and would discard any messages received from it.

-

System clocks are not guaranteed to be synchronized and thus can’t be used to order messages. Lamport Clock numbers are updated on writes only and are passed with the messages to solve conflicts by choosing the most recent update. This doesn’t help detect concurrent writes between different servers, in which case, version vectors are a more adequate solution.

-

Fault-Tolerant Consensus: Different algorithms like zab, Raft, and multi-Paxos are used to achieve the strongest consistency guarantees in distributed systems. Consensus refers to which data is stored, in what order, and when to make it visible to clients. Paxos relies on two-phase commit, quorum and generation clocks to achieve this. Achieving consensus on individual requests is not enough, as those requests need to be executed in the same order on all nodes.

-

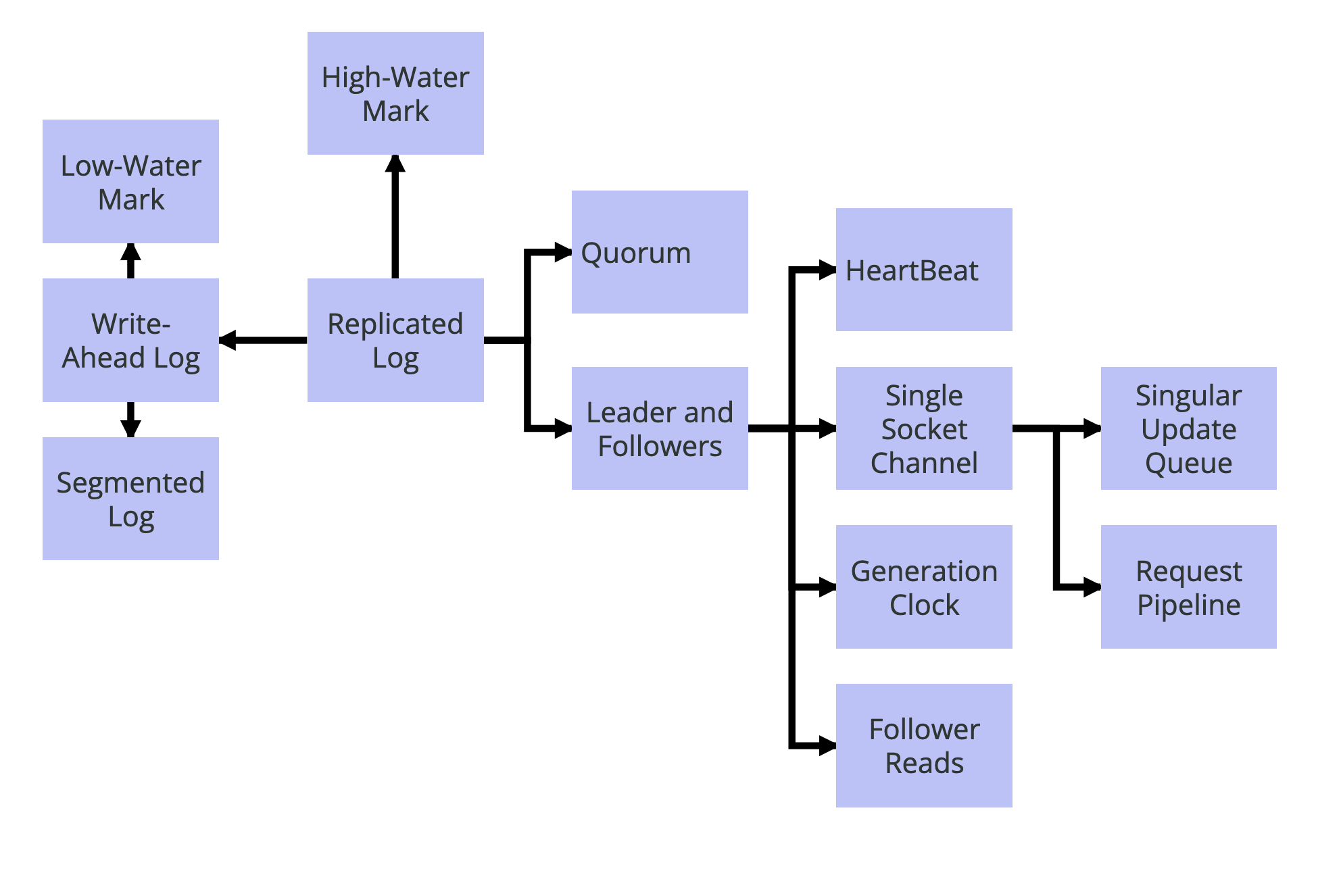

Replicated Log: This is achieved with a Leader-Follower model, using a Quorum to agree on updating the high-water mark that decides which values are now visible to clients. Reading is possible from the followers if stale values are tolerated. Requests are processed in a strict order, using a single-socket channel. Pipelining (sending multiple requests, without waiting for responses in-between) can be used to improve latency and throughput.

-

Atomic Commit: When data is too big to fit on a single node, partitioning schemes (eg. fixed, key ranges, etc,.) are used. To maintain fault tolerance, each partition uses Replicated Log across multiple nodes. A two-phase commit allows locking data to achieve atomicity, at the cost of throughput. Versioned values can be used in two-phase commit implementations to solve conflicts without using locks.

The Paxos Algorithm

-

Paxos is a family of algorithms for reaching consensus in Distributed Systems.

-

Consensus happens when a majority agrees on one proposed result, which will be eventually known by everyone.

-

Parties may agree on any result, not necessarily the one they proposed.

-

Consensus is needed in both leader-follower schema (consensus on leader election) and peer-to-peer schema (to guarantee consistency).

-

There are three roles: Proposers (Propose new values), Acceptors (Contribute to reaching consensus on new values), and Learners (Learn the agreed-upon value, eg. if they were late to the election). A node can play these roles at the same time.

-

Nodes can’t forget what they accepted (persistence) and they also need to know what a majority is.

-

A Paxos run aims to reach a single consensus. To reach another consensus, another Paxos run must happen.

-

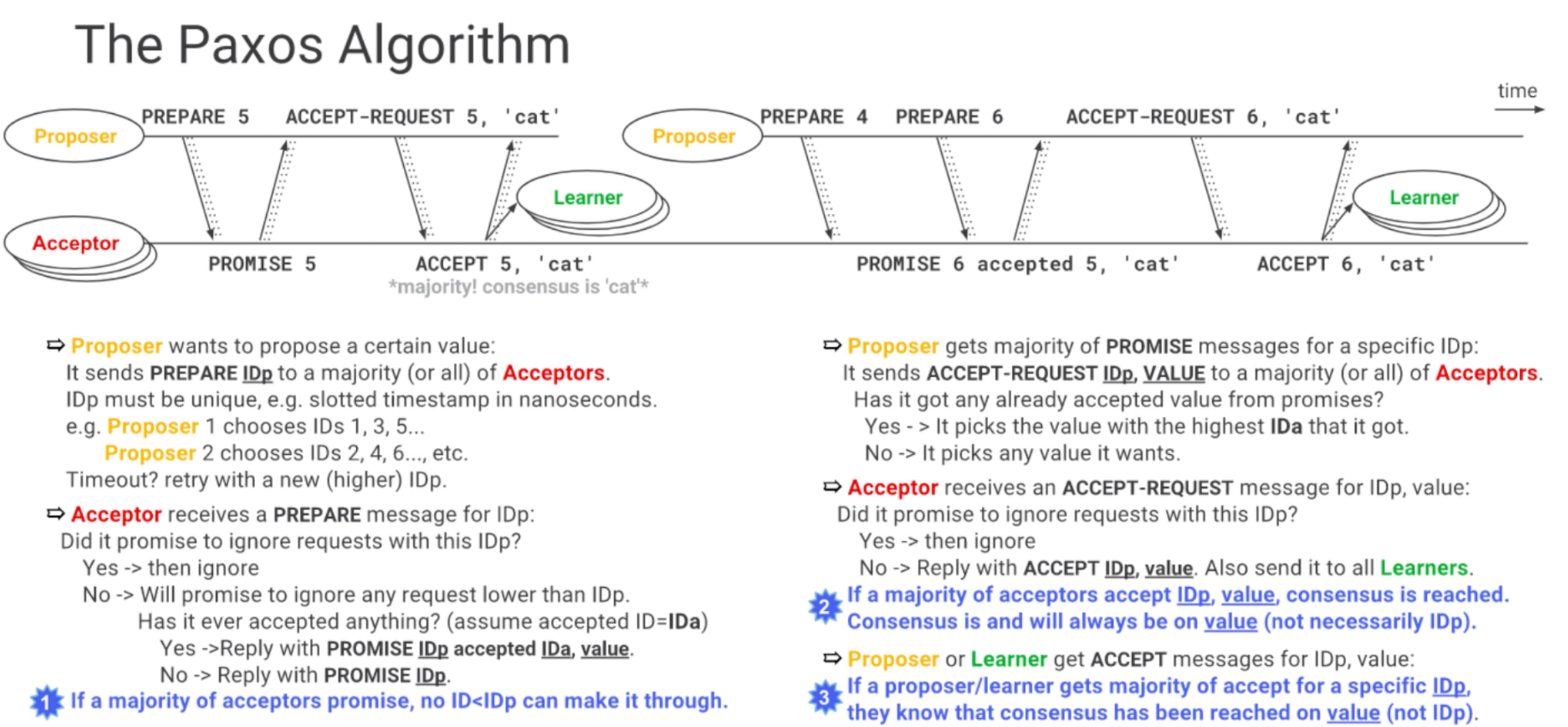

The election goes as follows:

- Proposer sends Propose message (with a unique IDp) to all/majority of acceptors. If timeout, propose a new higher IDp.

- If the acceptor accepts the proposal, it will reply with Promise IDp, and thus can’t accept any request lower than IDp. If a majority accepts, no ID < IDp will be accepted.

- On receiving a majority of Promises, the Proposer sends AcceptRequest IDp,Value.

- The Acceptor will reply with Accept IDp,Value, and also send it to all Learners.

- The consensus happens on the Value, not the IDp.

- If an Acceptor accepts a value and receives another Proposal with a higher IDp, it returns Promise IDp2,Accepted Value1. The 2nd Proposer will then send AcceptRequest IDp2,Value1. If there was no accepted value however (just a promise from the Acceptor to the first Proposer), the 2nd Proposer can choose any value they want.

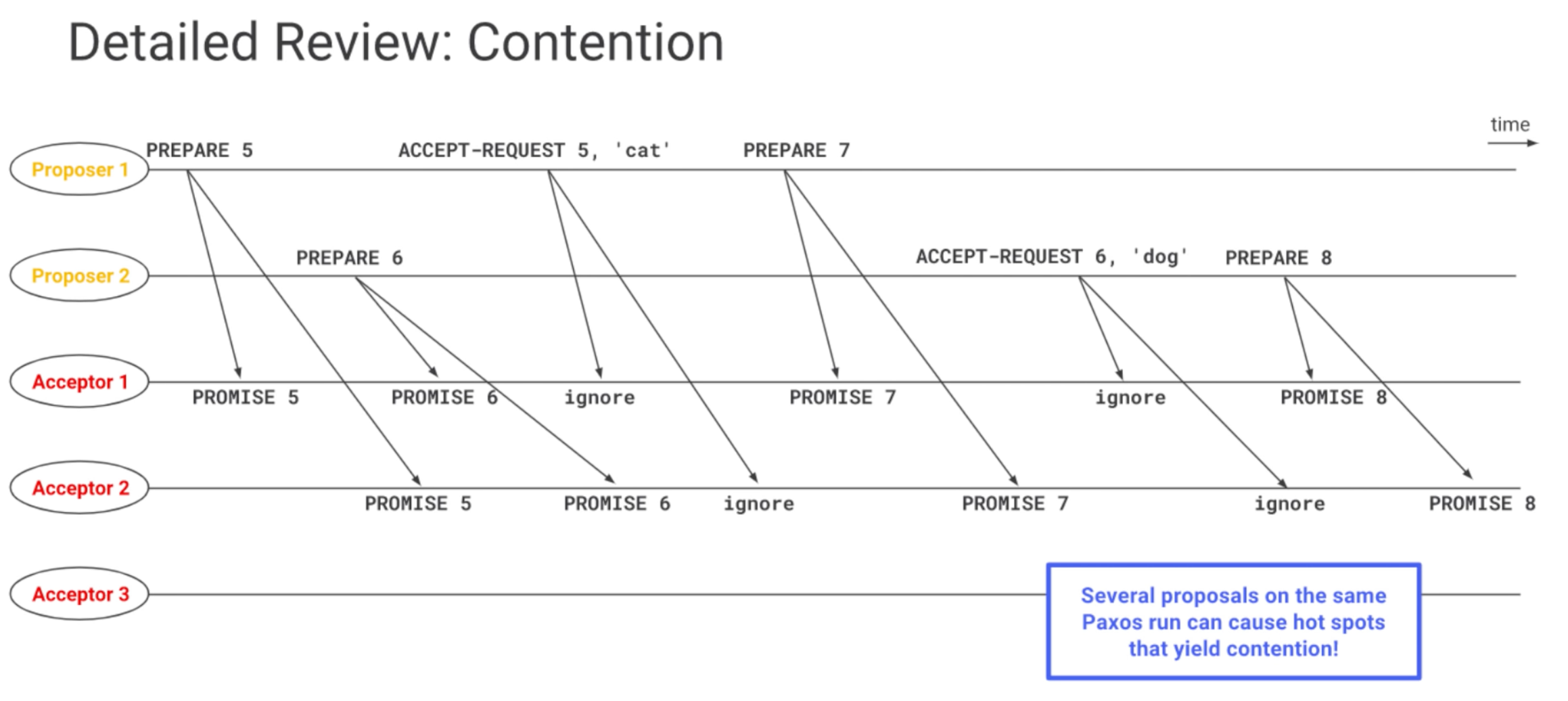

- There are risks of contention when two Proposers are stepping over each other, by continuously sending new Proposals with higher IDs, before the other Proposer’s Value is accepted. Exponential backoff can be used to alleviate this risk.